Relativistic beaming

Relativistic beaming (also known as Doppler beaming or the headlight effect) is the process by which relativistic effects modify the apparent luminosity of emitting matter that is moving at speeds close to the speed of light. In an astronomical context, relativistic beaming commonly occurs in two oppositely-directed relativistic jets of plasma that originate from a central compact object that is accreting matter. Accreting compact objects and relativistic jets are invoked to explain the following observed phenomena: x-ray binaries, gamma-ray bursts, and, on a much larger scale, active galactic nuclei (AGN). (Quasars are also associated with an accreting compact object, but are thought to be merely a particular variety of AGN.)

Beaming (short for relativistic beaming) affects the apparent brightness of something just as a lighthouse affects the appearance of its light source: the light source appears dim or unseen to a ship except when the lighthouse is directed towards a ship where it appears very bright. This so-called lighthouse effect illustrates how important the direction of motion (relative to the observer) is in relativistic beaming: if a blob of gas emitting electromagnetic radiation is moving towards the observer then it will be brighter than if it were at rest, but if the gas isn't moving towards the observer it may (in some cases) appear much fainter than if it were at rest. The importance of this effect in astronomy is illustrated by comparing the AGN jets detected in the galaxy M87 and 3C31 (see figures on the right). The twin jets in M87 show how beaming affects their appearance when one jet moves almost directly towards Earth and the other jet moves in the opposite direction. On one hand, M87's jet moving towards Earth is clearly visible to telescopes (the long and thin blue-ish feature in the top image) and is many times brighter due to beaming. On the other hand, M87's other jet is moving away from us and is, due to beaming, so much fainter than the jet directed towards us that it is rendered invisible.[1] 3C31 is different from M87 because both jets (labeled in the figure directly below M87's image) are directed at roughly right angles to our line of sight and are therefore subject to the same amount of beaming. Thus, unlike the case of M87, both of 3C31's jets are visible. The jet displayed on the upper part of the image of 3C31 is actually pointing slightly more in Earth's direction than the other jet and is therefore the brighter of the two.[2]

Relativistically moving objects are beamed due to a variety of physical effects. Light aberration causes most of the photons to be emitted along the object's direction of motion. The Doppler effect changes the energy of the photons by red- or blue-shifting them. Finally, time intervals as measured by clocks moving alongside the emitting object are different from those measured by an observer on Earth due to time dilation and photon arrival time effects. How all of these effects modify the brightness, or apparent luminosity, of a moving object is determined by the equation describing the relativistic Doppler effect (which is why relativistic beaming is also known as Doppler beaming).

Contents |

A simple jet model

The simplest model for a jet is one where a single, homogeneous sphere is travelling towards the earth at nearly the speed of light. This simple model is also an unrealistic one, although it does illustrate the physical process of beaming quite well.

Synchrotron spectrum and the spectral index

Relativistic jets emit most of their energy via synchrotron emission. In our simple model the sphere contains highly relativistic electrons and a steady magnetic field. Electrons inside the blob travel at speeds just a tiny fraction below the speed of light and are whipped around by the magnetic field. Each change in direction by an electron is accompanied by the release of energy in the form of a photon. With enough electrons and a powerful enough magnetic field the relativistic sphere can emit a huge number of photons, ranging from those at relatively weak radio frequencies to powerful X-ray photons.

The figure of the sample spectrum shows basic features of a simple synchrotron spectrum. At low frequencies the jet sphere is opaque. The amount luminosity increases with frequency until it peaks and begins to decline. In the sample image this peak frequency occurs at  . At frequencies higher than this the jet sphere is transparent. The luminosity decreases with frequency until a break frequency is reached, after which it declines more rapidly. In the same image the break frequency occurs when

. At frequencies higher than this the jet sphere is transparent. The luminosity decreases with frequency until a break frequency is reached, after which it declines more rapidly. In the same image the break frequency occurs when  . The sharp break frequency occurs because at very high frequencies the electrons which emit the photons lose most of their energy very rapidly. A sharp decrease in the number of high energy electrons means a sharp decrease in the spectrum.

. The sharp break frequency occurs because at very high frequencies the electrons which emit the photons lose most of their energy very rapidly. A sharp decrease in the number of high energy electrons means a sharp decrease in the spectrum.

The changes in slope in the synchrotron spectrum are parameterized with a spectral index. The spectral index, α, over a given frequency range is simply the slope on a diagram of  vs.

vs.  . (Of course for α to have real meaning the spectrum must be very nearly a straight line across the range in question.)

. (Of course for α to have real meaning the spectrum must be very nearly a straight line across the range in question.)

Beaming equation

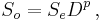

In the simple jet model of a single homogeneous sphere the observed luminosity is related to the intrinisic luminosity as

where

The observed luminosity therefore depends on the speed of the jet and the angle to the line of sight through the Doppler factor,  , and also on the properties inside the jet, as shown by the exponent with the spectral index.

, and also on the properties inside the jet, as shown by the exponent with the spectral index.

The beaming equation can be broken down into a series of three effects:

- Relativistic aberration

- Time dilation

- Blue- (or Red-) shifts

Aberration

Aberration is the change in an object's apparent direction caused by the relative transverse motion of the observer. In inertial systems it is equal and opposite to the light time correction.

In everyday life aberration is a well known phenomenon. Consider a person standing in the rain on a day when there is no wind. If the person is standing still, then the rain drops will follow a path that is straight down to the ground. However if the person is moving, for example in a car, the rain will appear to be approaching at an angle. This apparent change in the direction of the incoming raindrops is aberration.

The amount of aberration depends on the speed of the emitted object or wave relative to the observer. In the example above this would be the speed of a car compared to the speed of the falling rain. This does not change when the object is moving at a speed close to  . Like the classic and relativistic effects, aberration depends on: 1) the speed of the emitter at the time of emission, and 2) the speed of the observer at the time of absorption.

. Like the classic and relativistic effects, aberration depends on: 1) the speed of the emitter at the time of emission, and 2) the speed of the observer at the time of absorption.

In the case of a relativistic jet, beaming (emission aberration) will make it appear as if more energy is sent forward, along the direction the jet is traveling. In the simple jet model a homogeneous sphere will emit energy equally in all directions in the rest frame of the sphere. In the rest frame of Earth the moving sphere will be observed to be emitting most of its energy along its direction of motion. The energy, therefore, is ‘beamed’ along that direction.

Quantitatively, aberration accounts for a change in luminosity of

Time dilation

Time dilation is a well-known consequence of special relativity and accounts for a change in observed luminosity of

Blue- (Red-) shifting

Blue shifting (or red shifting) can change the observed luminosity at a particular frequency, but this is not a beaming effect.

Blue-shifting accounts for a change in observed luminosity of

Lorentz invariants

A more-sophisticated method of deriving the beaming equations starts with the quantity  . This quantity is a Lorentz invariant, so the value is the same in different reference frames.

. This quantity is a Lorentz invariant, so the value is the same in different reference frames.

Terminology

- beamed, beaming

- shorter terms for ‘relativistic beaming’

- beta

- the ratio of the jet speed to the speed of light, sometimes called ‘relativistic beta’

- core

- region of a galaxy around the central black hole

- counter-jet

- the jet on the far side of a source oriented close to the line of sight, can be very faint and difficult to observe

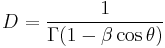

- Doppler factor

- a mathematical expression which measures the strength (or weakness) of relativistic effects in AGN, including beaming, based on the jet speed and its angle to the line of sight with Earth

- flat spectrum

- a term for a non-thermal spectrum that emits a great deal of energy at the higher frequencies when compared to the lower frequencies

- intrinsic luminosity

- the luminosity from the jet in the rest frame of the jet

- jet

- a relativistic jet of plasma emanating from the polar direction of an AGN

- observed luminosity

- the luminosity from the jet in the rest frame of Earth

- spectral index

- of measure of how a non-thermal spectrum changes with frequency, the smaller α is the more significant is the energy at higher frequencies, typically α is in the range of 0 to 2

- steep spectrum

- a term for a non-thermal spectrum that emits little energy at the higher frequencies when compared to the lower frequencies

Physical Quantities

- angle to the line-of-sight with Earth

- jet speed

- intrinsic luminosity

(sometimes called emitted luminosity)

(sometimes called emitted luminosity)- observed Luminosity

- spectral index

where

where

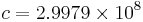

- Speed of light

m/s

m/s

Mathematical Expressions

- relativistic beta

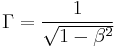

- Lorentz factor

(often written as

(often written as  and referred to as relativistic gamma)

and referred to as relativistic gamma)- Doppler factor

See also

- List of plasma (physics) articles

- Relativistic jet

- Relativistic particle

- Relativistic plasma

- Relativistic similarity parameter

- Relativistic wave equations

References

- ^ Sparks et al., W. B. (1992). "A counterjet in the elliptical galaxy M87". Nature 355 (6363): 804–806. Bibcode 1992Natur.355..804S. doi:10.1038/355804a0.

- ^ Laing, R.; A. H. Bridle (2002). "Relativistic models and the jet velocity field in the radio galaxy 3C 31". Monthly Notice of the Royal Astronomical Society 336 (1): 328–352. arXiv:astro-ph/0206215. Bibcode 2002MNRAS.336..328L. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05756.x.